This post is a student response to Thomas Tobin’s webcast on Universal Design of Learning as well as the UDL Guidelines page from UDL’s website. For more information, please visit those sites.

In his webcast on the basics of UDL, Thomas J. Tobin of the University of Wisconsin-Madison made it clear that we need to re-frame how teaching institutions approach UDL and accessibility. When presented with students who desire accommodations for their learning, instructors, though willing to comply, can often feel frustrated and stressed at the prospect of altering curriculum to fulfill the request.

But, UDL is not only a disability or access services format. Rather, UDL is a proactive way to structure material to help make the interactions the happen at your institution more easily accessible for people on their mobile devices.

What is UDL?

UDL is defined as a framework to improve and optimize teaching and learning for all people based on scientific insights into how humans learn. There are three components:

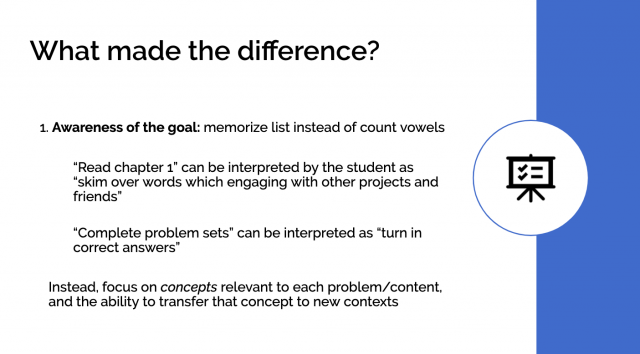

- We need multiple ways to keep learners engaged. This is the “why” of learning. For example, instructors could give a time estimate for an assignment so that students know how to self-regulate their approach to the assignment, and experience autonomy.

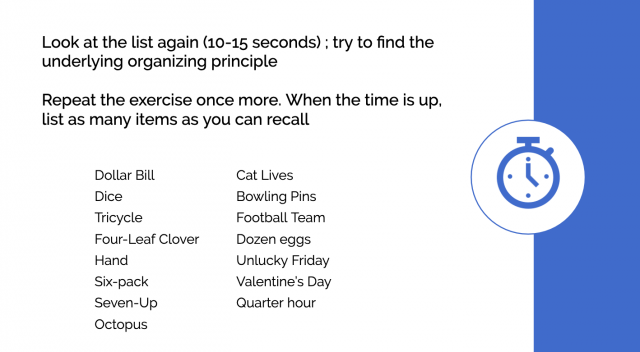

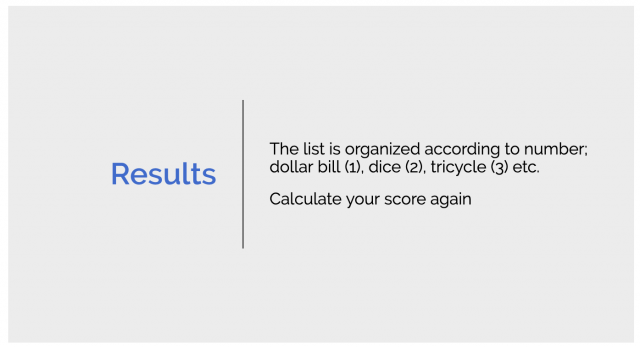

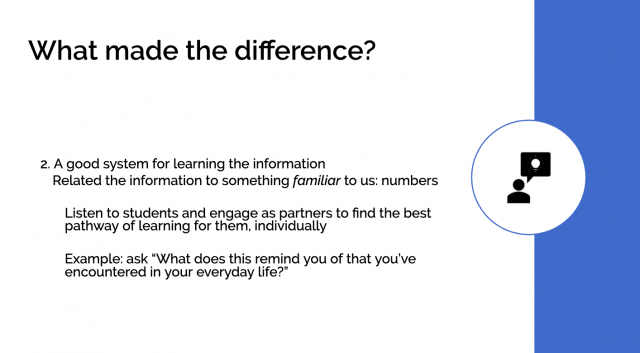

- We need multiple ways of representing information. This is the “what” of learning. For example, the students can be presented with both audio and visual versions of the content, and choose which style works best for them to retain the information. Providing different options for the information display allows deeper comprehension for the student, as they may understand one form of communication better than another.

- We need multiple ways to give people choices for their actions. This is the “how” of learning. For example, as long as learning objectives remain the same, you can offer multiple ways for the student to complete an assignment, perhaps through an essay or visual presentation option. Or, give multiple options for first drafting that point toward the same end result assignment.

Realistic Implementation

UDL helps to understand what has to happen at the level of course design that makes accommodation less necessary.

UDL is “plus one” learning. If there is a way you interact with students, just make one more way to interact with materials, each other, and the wider world.

Remember that UDL reduces barriers by offering students choices and control. If you offer more ways for students to access material, they are more likely to persist in classes, more likely to be retained in later years, and more likely to be satisfied with their learning experience.

UDL is work, but will alleviate more work and stress that could potentially arise later in the course, as it is a proactive, not reactive format.

Many instructors are familiar with DI, or “differentiated instruction”. DI is customizing the instructor’s response to the student in any way they can. DI occurs in the moment, responding to a specific student situation. It is also reactive, allowing instructors to hear and respond. UDL is the proactive counterpart to DI, and happens on “day 0” to set up for success.

5 strategies for UDL:

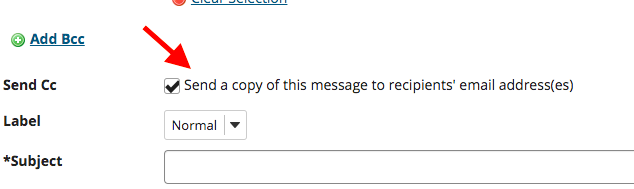

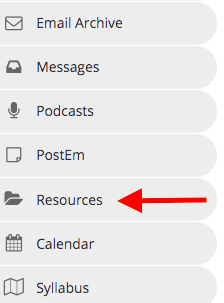

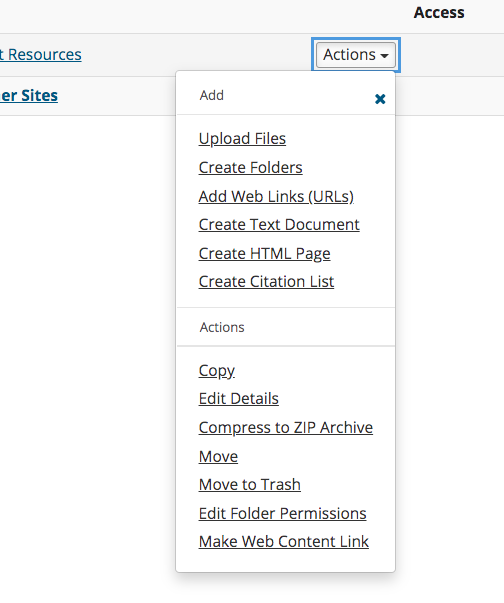

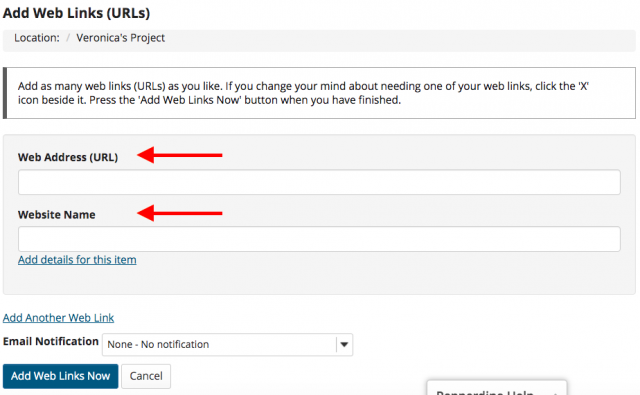

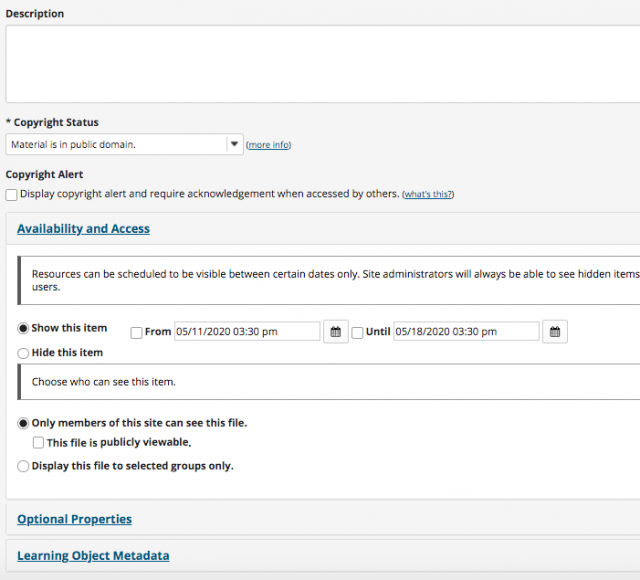

- Start with text. Use your written content as a script for audio/podcast or video. You can post the text version and video/audio as the alternative (multiple ways to represent information).

- Make alternatives. You can offer different formats for print/PDF content, or post take still photos with captions from a video. This reduces cognitive barriers for students. Note: UDL does not aim to water down content, but instead makes it easier for the student to get in and do it.

- Let them do it their way. As long as objectives for assignment are the same, could offer video or paper presentations, let the student choose.

- Go step by step. 10:2 ratio. Give info for 10 mins, then ask students to respond for 2 mins. The response does not even need to be related to the info, it is used as a pause to retain info given in the 10 minutes.

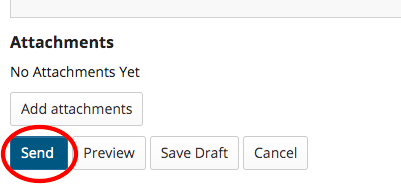

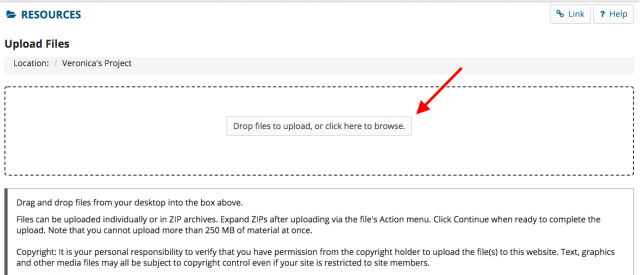

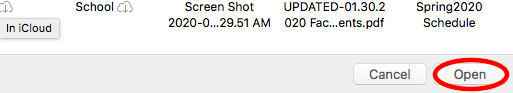

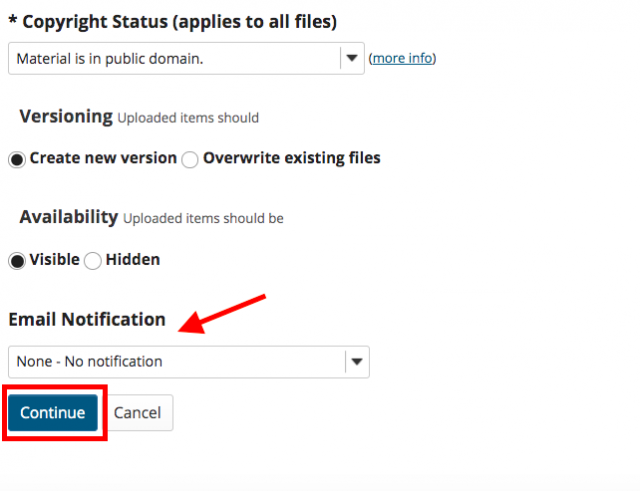

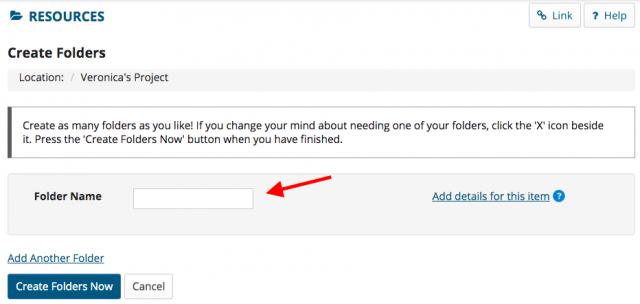

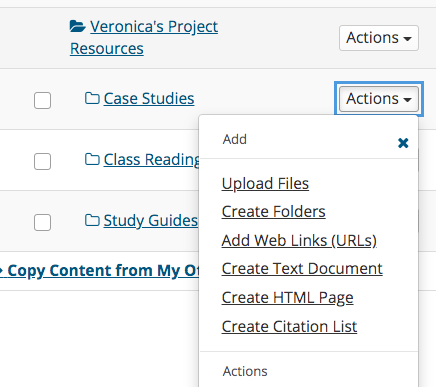

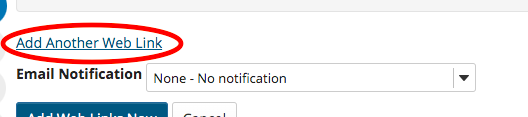

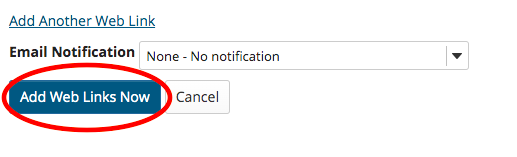

- Set content free. Publish content on platforms that are mobile accessible. Also, make sure they are not tied to a specific software that the student has to download or buy.

FAQs

What about the science surrounding different learning styles?

Learning styles, in the conventional sense, (audio verses visual presentation, etc.) don’t exist. At least, not as six characteristics. Our learning preferences change from moment to moment based on the content and circumstances. For example: a man who is taking a class but also has to drop his daughter off at school before work may prefer an audio version of the class content to listen to during his commute, and in that instance, an audio option is much more helpful to him than a PDF.

Retention also varies and is not based on hard principles but based on accessibility; if the student can get to the information, look through it multiple times, and customize how they move through it, they can retain it.